In the 1400s, a man named Johannes Gutenberg, a resident of the German city of Mainz, invented a machine to quickly reproduce written materials, using metal stamps to transfer ink to paper in a single pressing. This innovation, the printing press, marked the start of what has become known as the Printing Revolution, the first step down the path towards the age of Mass Information in which we now live.

The Gutenberg Printing Press, Meggs, Philip B. A History of Graphic Design. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1998. (p 64).

In the 1970s, the name Gutenberg once more resurfaced, when a man named Michael Hart, working on a computer system at the University of Illinois, typed up a digital version of the Declaration of Independence; the first ebook. Hart’s work eventually led to the founding of Project Gutenberg, an organization devoted to the production and distribution of free, public domain eBooks over the internet.

But for most people, eBooks are more heavily associated with a different company: Amazon. Founded in 1994 by Jeff Bezos, Amazon was not always the universal online marketplace we know today. When the company first started, it sold one thing and one thing only – books. According to a Business Insider article on the company’s history, “In the early days of Amazon, a bell would ring in the office every time someone made a purchase… It only took a few weeks before the bell was ringing so frequently that they had to turn it off.”

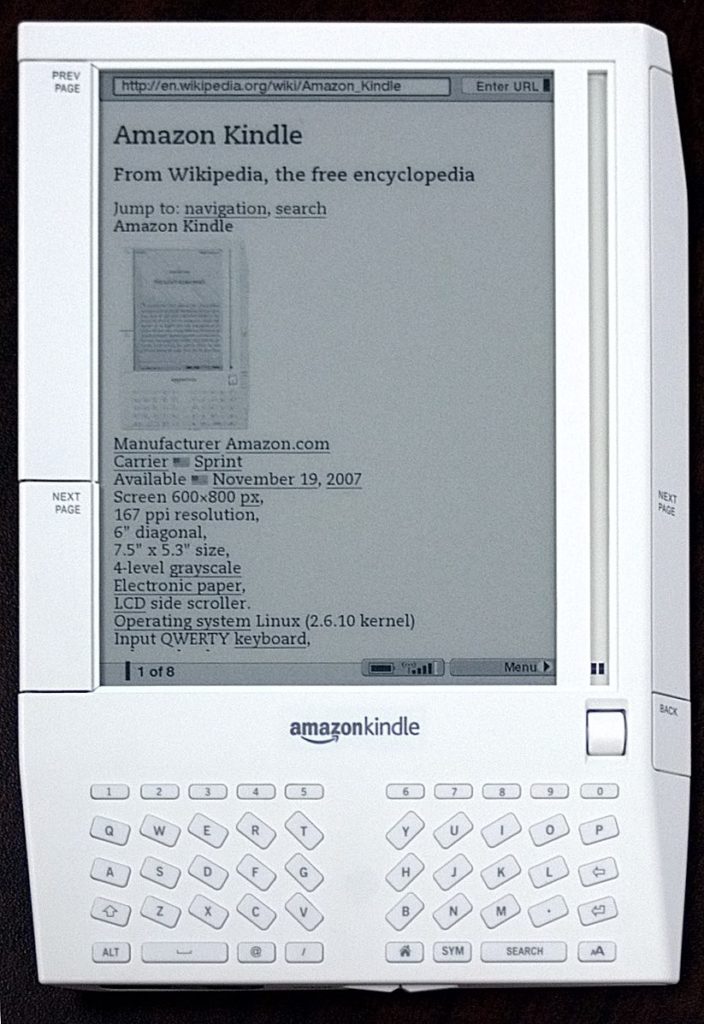

By the late 1990s, Amazon had expanded into new realms of commerce, selling electronics of all kinds, including toys, games, and consumer electronics. However, the company’s connection to books remained, and in October of 2007, Amazon launched the Kindle, the first successful ebook reader on the market (launched after a few false starts, including the Rocket eBook and the 2006 Sony Reader).

Amazon Kindle, First Generation, Image by Jon ‘ShakataGaNai’ Davis.

Before the Kindle’s release, reading eBooks was a not a challenge for the faint of heart. Consumers had to juggle numerous, often conflicting formats, and find apps to turn those files into readable text. Once those files were finally readable, the overwhelming majority of people were then left tethered to a desk, unable to take their newly downloaded books beyond the confines of their homes and offices.

What the Kindle brought to the table was an ecosystem, an established pipeline easily accessible to the computationally challenged, a price cap of $9.99 on all books, and a slick, long-lived device. Now buying an ebook was as easy as visiting Amazon’s store from your new device, hitting the buy button, and waiting for the download to finish. Back in those days, the Kindle was directly tied into Sprint’s EV-DO network, so books could be downloaded almost anywhere in the continental United States. For those abroad, eBooks could also be downloaded and transferred to the device through an included data wire.

One of the devices hallmarks, and a feature that remains a key part of the Kindle line-up to this day, was its screen. Instead of a more typical LCD screen, Amazon’s Kindles use what’s known as an e-ink display. On a very basic level, that means that images on a Kindle are in black and white, they have no backlight, and they are created by rearranging actual ink within the screen using electric currents. Using an e-ink display also extends the devices battery life far beyond that of those with more standard screens.

The system quickly improved, and Amazon released a second version a little over a year later, in the early months of 2009. As the market for full-fledged tablets grew, spurred in large part by the release of Apple’s iPad in 2010, Amazon expanded the Kindle line to include the Fire, a full tablet running a version of Google’s Android operating system.

At present, Amazon has become synonymous with eBooks in the minds of consumers, though smaller businesses like Gutenberg continue to persist, alongside competitors like Barnes and Noble. However, Amazon’s dominance in the market is undeniable. According to a Forbes article from 2014, Amazon’s ebook revenues have exceeded $530 million a year, and the number of Kindle owners likely number in the tens of millions.

The rise of eBooks has led many to claim that print is dead, a victim of technological progress and a shrinking number of brick-and-mortar bookstores. There is an equally large number of articles claiming precisely the opposite, that, in the words of a BBC article published in 2015, “the book isn’t dead; technology is simply helping it evolve beyond its physical confines. Long live the book.”

Let’s take a look at some data. The U.S. Economic Census only collects data on years ending in 2 and 5, so we’re a bit constrained in terms of measuring more recent figures and trends. However, between 2002 and 2012, the number of bookstores in the U.S. dropped from 10,860 to 7,176. In other words, almost a third of bookstores closed down over the course of a decade. Similarly, the number of people employed by bookstores declined from 133,484 in 2002 to 89,933 in 2012; a 32% drop.

30% is a sharp decline by anyone’s measure, and, though data is somewhat limited, sales of eBooks seem to have held strong throughout this period and into the modern day. However, recent data suggests that trend may well be changing. That reversal, however, may have less to do with a return to print, and far more to do with the continued rise of multi-use devices, including tablets and smartphones.

Whether you prefer reading on a Kindle, on a tablet, or with pages between your fingers, our desire to consume written media seems to have changed little over the centuries, though the ways we produce that media will likely continue to grow and evolve.

You must be logged in to post a comment.